Your cart is currently empty!

Владімір (Зеев) Жаботинський i українське питання

In this book, the journalist and historian Israel Kleiner invites the reader to consider an old problem—the history of Ukrainian-Jewish relations—from a fresh perspective. The eminent Zionist leader Vladimir (Ze’ev) Jabotinsky (1880–1940) is well known for his role in Jewish political history, but his writings on the Ukrainian question and his relations with Ukrainian politicians […]

Out of stock

Description

In this book, the journalist and historian Israel Kleiner invites the reader to consider an old problem—the history of Ukrainian-Jewish relations—from a fresh perspective. The eminent Zionist leader Vladimir (Ze’ev) Jabotinsky (1880–1940) is well known for his role in Jewish political history, but his writings on the Ukrainian question and his relations with Ukrainian politicians have not been the subject of extensive scholarly research. Jabotinsky, who was born in Odesa, worked as a journalist in that city and witnessed the crisis developing in the Russian Empire as a result of the unrelenting policy of official Russification. As the empire’s non-Russian peoples began to mobilize for political and cultural autonomy, there was an increasingly violent reaction from Russian forces, which instigated anti-Jewish pogroms and called for discrimination against inorodtsy (non-natives). Unlike most Jewish leaders of the period, Jabotinsky believed that Ukraine was crucial to the empire’s future: the growing Ukrainian movement was powerful enough to break the wave of Russification, and its political orientation would help determine whether the post-imperial order proceeded in the direction of freedom or tyranny. Well aware that most of the empire’s secular Jewish elite was culturally Russified and active mainly in Russian political organizations, Jabotinsky advocated a reorientation. If an accommodation were not reached between the Jewish and Ukrainian movements, he warned, the Ukrainian masses might be swayed by reactionary elements who would persuade them that Jews were their political enemies. The pogroms of 1919 in Ukraine confirmed the validity of Jabotinsky’s fears. Nevertheless, he did not break his ties with democratic Ukrainian politicians: in 1921 he signed an agreement with his old friend Maksym Slavinsky, a representative of the Ukrainian People’s Republic government-in-exile, providing for a Jewish gendarmerie to defend the Jewish population against pogroms in the event of a new anti-Bolshevik campaign by Ukrainian forces. When the exiled leader of Ukraine’s government, Symon Petliura, was assassinated in 1926 by a Bessarabian Jew claiming vengeance for the victims of the pogroms, Jabotinsky did not join the wave of approval but pointed out that political benefit from the assassination would accrue to the newly established Soviet dictatorship. Often slighted as a marginal or eccentric figure, Jabotinsky emerges from this account as a thinker with a coherent view of nationalism and as an extraordinarily sensitive observer who often correctly foresaw the course of political developments. His fundamental principle of mutual respect nations provides a sound basis for the development of relations among Ukrainians and Jews.

Additional information

| Weight | 1 kg |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 23 × 15.5 × 2 cm |

| Author | |

| Format | Hardcover |

| Language | Ukrainian |

| Year Published | 2009 |

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

You may also like…

-

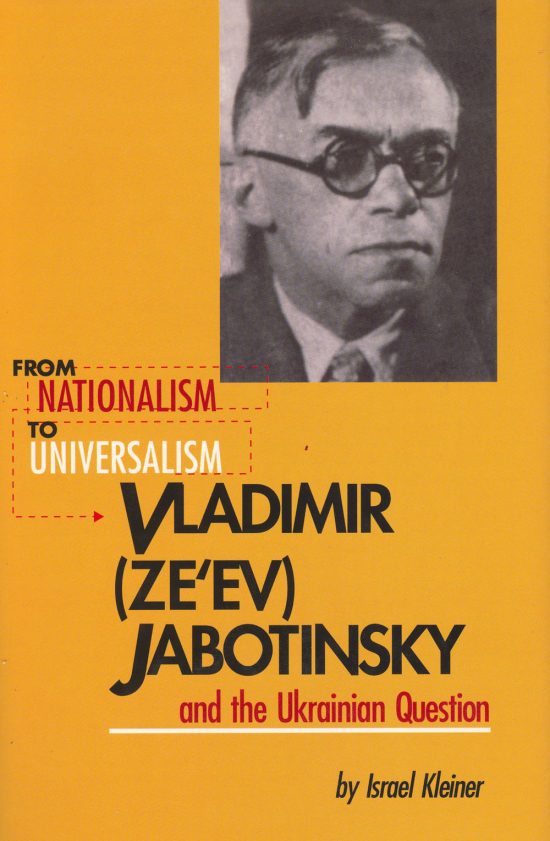

From Nationalism to Universalism: Vladimir (Ze’ev) Jabotinsky and the Ukrainian Question

Price range: $29.95 through $49.95 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective (Third Edition)

Price range: $39.95 through $69.95 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Україна Модерна, No. 24, 2017

$14.95 Add to cart

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.